Phone Min Thant, Simon Fraser University | August 14, 2025

Understanding Casualties Beyond the Battle

How better research coordination can improve VAC-CAF’s Joint Veterans’ Suicide Prevention Strategies

home / policy briefs / phone min thant

time to read: 13 min

Executive Summary

In Canada, veterans experience 1.5 to 2 times higher risks of death by suicide than the civilian population (VanTil et al., 2021). The causes of this include service-related mental and physical challenges as well as problems arising from transitioning back to civilian lifestyles. The persistent issue of veteran suicide rates highlights a critical gap in knowledge sharing between the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and Veterans Affairs Canada (VCA). Analysis of the current data suggests the following concerns:

A scarcity of research materials on Canadian veterans’ suicide.

A general lack of focus on the social determinants of suicide.

A disconnect in research on suicidality between service members and veterans.

Improved research coordination between the CAF and the VAC with the aid of outside stakeholders, who can help mitigate negative trends, is recommended. The focus should be on the socio-economic and location-related factors that are driving suicide. Further recommended is the formation of a central data repository between these two government institutions. With these foundational steps in place, it is suggested that the CAF explore more bottom-up, research-informed approaches to veteran suicide prevention, ultimately aiming to make beneficial suicide prevention programs more accessible to all Canadian veterans.

Introduction: Veteran Suicide in Canada

Canadian veterans are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to die by suicide than the civilian population (VanTil et al., 2021). This death rate has remained consistent since 1976 (VanTil et al., 2021). Considering that the CAF and the VAC are both under immense pressure from the public due to cases related to poor administrative management, discipline breakdowns, and legal battles, these mortality rates are particularly alarming (Raycraft, 2022; Brewster, 2022; Brewster 2024).

The issue of veteran suicide stands at risk of becoming an unwanted “second front” for both the CAF and the VAC. These institutions must recognize the failures in their current strategies, increase their knowledge on veteran suicide, and design policies that consider the perspectives and concerns of the veterans themselves. While it is well understood that casualties occur beyond the battle, research on the reasons behind this remain inadequate and underappreciated, hindering effective policymaking. By submitting this brief to the CAF and the VAC's research and policy teams, we demonstrate how better research coordination can serve as a crucial baseline for policy advancements and offer an opportunity to present concrete implementation strategies.

Key Problem: A Lack of Research Coordination

The key to addressing veteran suicide in Canada is creating policies that are informed by data-driven research. The current lack of a coordinated research body for the CAF and VAC or between these organizations and private research and medical institutions has created three main issues:

A general scarcity of data on veterans’ suicide in the Canadian context.

Am imbalance in the focus of existing research on psychological and social factors behind veteran suicidality.

Research on overlapping topics with little information-sharing between the two main research organizations.

It is imperative that we see an improvement in coordination on veteran suicide research, bridge the current disconnect between veterans’ and service members’ suicide, and expand how data is obtained by considering variables such as location, socio-economic status, and racial and ethnic differences between veterans experiencing suicide. This research coordination and the subsequent incorporation of data in a more comprehensive report will aid these institutions in formulating more accessible suicide mitigation policies.

Analysis of Current Data

Quantitative Data

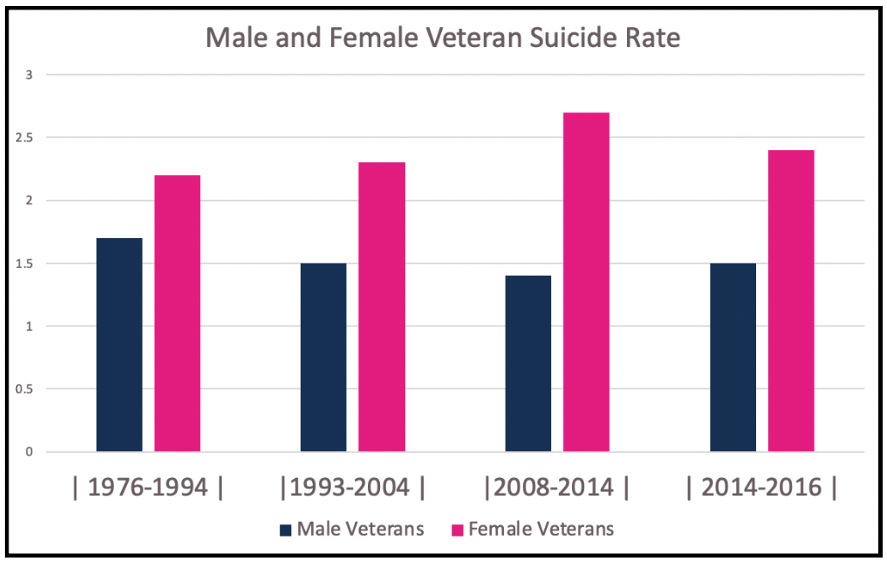

Canadian veterans are at a 1.5 to 2 times higher risk of dying by suicide compared to the Canadian General Population (CGP). Moreover, female veterans experience a suicide risk 0.6 times higher than that of their male counterparts. The highest suicidality is observed in those below 30 who held non-commissioned ranks (VanTil et al., 2021).

Figure 1: Ratio of Canadian male and female suicide rates compared to the Canadian general population (CGP) from 1976-2016 (VanTil et al., 2021).

There are also regional variations. For instance, in Ontario, veteran suicide rates remain similar to that of the CGP (Mahar et al., 2019). However, regional data remains limited for further comparison. In addition to actual rates of suicide, a CAF psychological survey (CCHS, n.d.) indicated that a staggering 15.4% of CAF respondents experiences suicidal ideation, and 2.3% of this group made at least one attempt to take their own lives during service (Brunet & Monson, 2014). In a more extensive CAF survey, also by Bruent and Monson (2014), it was found that 38.5% of the ideators developed a suicide plan, and 34% went through with those plans within a year. These rates are four times higher in members experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from combat.

Canadian veteran suicide rates suggest immense mental pressure from service. This pressure continues as veterans experience difficulties readjusting to civilian lives post-service, contributing to suicidality. However, CAF and VAC data predominantly focuses on military deployment and mental health; rarely differentiating between socio-economic factors (e.g., economic class, ethnic backgrounds, and substance use) affecting members studied or whether the population studied are veterans or actively in-service.

Causes of Veteran Suicide in Canada

Veteran suicide is associated with both service-related trauma and difficulties re-adjusting to civilian lives post-service. Service-related traumas include mental and physical health conditions, such as PTSD and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) (Brunet & Monson, 2014; Ghobrial, 2024). These health conditions contribute to suicidal ideation (Brunet & Monson, 2014; Ghobrial, 2024).

Another contributing factor is the military’s attitude towards suicide. While the CAF has made progress in acknowledging military-related suicides, recent trends in commemorating these deaths as battlefield honours inadvertently overlook the suicides of non-deployed veterans (Barrett & English, 2014).

Veterans also experience greater suicidal ideation from transition-related issues when returning to civilian life. The majority of these transition-related issues come from scarcity of shared values and lack of a sense of community. The former relates to difficulties fitting into the less regimented civilian lifestyle and the latter is about not being able to identify with any particular social group post-transition. Veterans experiencing both of these issues have the highest risk of suicidal ideation. Integral to policymakers, however, is the observation that suicidal ideation is not elevated when veterans can connect with others of similar social beliefs online (e.g., connecting via a veterans’ association on social media) despite lacking a sense of community belonging in their civilian lives (Thompson et al., 2019).

Research Scarcity

The most comprehensive data published on this topic is the VAC’s Annual National Veterans’ Suicide Report (VanTil et al., 2021). This report is supported by numerous public research funds, most notably from the CAF (VanTil et al., 2021). As previously mentioned, a predominant shortcoming of this research model is that it lacks consideration of relevant social variables to test policy initiatives across the board. It particularly lacks focus on the location-related and socio-economic variables which are known for driving suicide rates. It also lacks involvement from local governments when engaging in policymaking. Moreover, this model predominantly focuses on psychological research and mental health initiatives, ignoring the socio-economic causes of suicide.

These issues have also created a failure in intersectional thinking about the link between a potential lack of mental health services, regional variation (rural versus urban) and socio-economic differences (affordability of services), which may have an effect on rates of suicidal ideation among veterans (Jalles & Andresen, 2015; Kirkbride et al., 2024). This failure not only explains Canada’s insistent focus on a single national strategy and a lack of decentralized policymaking on veteran suicide since 2017, but also why the strategy remains predominantly focused on mental-health action and research.

In addition to these factors, the CAF and the VAC also suffer from a disconnect in their research. The CAF’s investigations on suicide focus on deployment-related trauma and personal circumstances of service members experiencing suicide. However, they lack focus on the relationships between such issues and veterans’ suicide. The VAC’s official reportage appears to have more quantitative data that lacks significant analyses on the veterans’ military trajectories and the impact this might have on suicidality (Berthiaume, 2019). Therefore, there is a significant research gap in the relationship between the veterans’ experiences in the military, post-service factors, and the likelihood of dying by suicide or experiencing suicidal ideation (Brunet & Monson, 2014; Mahar et al., 2019).

At the core of this issue, there is an absense of a coordinated research repository, proper information sharing mechanisms, data standardization, and cooperation guidelines (Rudnick et al., 2022). These factors impede joint suicide-prevention strategies and attribute to a top-down approach in which services for veterans mainly come from the federal government staff – a model vulnerable to detachment from veterans’ voices and experiences.

Recommendations

More coordinated research on the social factors behind veteran suicide

Given the relative scarcity of research materials on veteran suicide in Canada, the first step is to improve the CAF-VAC suicide prevention strategy. This can be done by enhancing the quality and quantity of research dedicated to promoting policy action. Fulfilling this task falls to the Research Directorate of the VAC and the Surgeon General of the CAF (the main coordinators of research on veteran and military suicide in Canada). The following three objectives must be fulfilled:

Establish the effect of location (e.g., regional variations, rural-urban divides) and related social determinants of veterans’ suicide (both in terms of ideation and actual cases).

Publish more comprehensive annual reports on veterans’ suicide which include the factors outlined above.

Connect the divide between service-members’ and veterans’ suicides more firmly, pinpointing how deployment and service-related traumas influence post-service drivers of suicidality.

Fulfilling these three goals involves modifing and enlarging the current CAF-VAC research methodology. It should first compile datasets from sources other than the Defence Department pay system (VanTil et. al, 2021). Partnerships with Veteran NGOs, clinics and private/public mental health researchers are helpful, as shown by the comprehensiveness of the data-collection methods used by the US Veterans’ Affairs Department (USVA) (US Department of Veterans’ Affairs, 2023). More work is also needed in the current Canadian death certificate-analysis model to match the data between the veterans, cause of death, and location of residence.

Since this model is similar to that of the USVA, the CAF-VAC researchers will need to incorporate the study of location in their data, as done by Mahar et. al (2019) in their study of veteran suicides in Ontario. Enlargement of data-collection methodologies is also critical for studying the socio-economic variables behind veterans’ suicide. Relying on the administrative pay system alone has its advantage of simplicity but does not have any relevance to the individual characteristics of the veterans themselves such as ethnicity, socio-economic status, and post-service employment, which are all drivers of suicidal ideation (Jalles & Andresen, 2015). Statistics Canada should play a central role in coordinating these research efforts with an expanded partner base, particularly with those in healthcare and the private sector.

Lastly, research funds also needs to be allocated to bridging the gap between research on service members’ and veterans’ suicides. Greater cooperation between the CAF and the VAC is important to achieve this goal, as the former’s research on deployment-related trauma and personal circumstances of service members involved in suicides (Berthiaume, 2019) can complement the VAC’s on-going studies of veterans.

The key aspects in resolving this issue are:

Creating a joint central data repository on veterans’ suicide (Rudnick et al, 2022).

Establishing a mechanism for sharing information between the two institutions (Rudnick et al., 2022).

Making these changes will help these organizations agree on standardized research methods and data-presentation. It will also help them solidify guidelines, making research cooperation easier. Furthermore, creating a joint website on veterans’ suicide prevention to replace the different CAF and VAC websites may be helpful in centralizing research data and increasing its accessibility. This centralization process will be particularly important once research collaboration takes place with organizations outside of the public sector.

Figure 2: Comparison charts of current VAC-CAF research and data-sharing mechanisms, and mechanisms recommended in this policy brief.

Once relevant data is obtained, the publication team should follow USVA’s annual reports template. Following this template will allow them to create better trend-based graphics, assess the effectiveness of on-going policies, and help inform successful action in the future. The VAC’s reporting should also incorporate a progress review of its policies, reducing the disconnect between objective research and policymaking and increasing the accessibility of information on veterans’ well-being. Such a review could also put pressure on VAC policymakers to be more accountable and transparent.

The first potential hurdle in pursuing this policy is the need to balance data-collection and concerns for privacy, particularly when non-government organizations are involved. The VAC’s current challenges suggest a careful handling of this legal and moral obstacle (Brewster, 2024). Skepticism on how data collected by different agencies is used is particularly strong among Canadian senior citizens, a demographic which is heavily populated by veterans (Cooper et al., 2017; Government of Canada, 2024). However, this suspicion is primarily rooted in financial mistrust and there is a generally positive view towards data-collection that aims to help vulnerable demographics (Cooper et al., 2017). Therefore, transparent guidelines and an emphasis on veteran support may help mitigate this challenge (Cooper et al., 2017). There is also the threat of research overlap causing confusion between public research bodies with non-government researchers. Avoiding this threat involves sequencing data coordination only after an establishment of a central data repository. Finally, increased research coordination may counter budget-downsizing initiatives that are at the core of the VAC’s yearly plans (Government of Canada, 2024). Outsourcing research funding to outside organizations is key to easing this challenge.

Compiling such a large amount of data will also pose challenges to existing protocol, particularly when it comes to segregating national data into regional categories with new socio-economic sub-categories. The USVA’s Assessing Social and Community Environments with National Data (ASCEND) research program took two years to complete (US Department of Veterans’ Affairs, 2023). Since the proposed Canadian study is similar in scope, involving many government and private partners, it will likely be difficult for the VAC to report annually on the issue. This is especially true since the Canadian study plans to diversify from its traditional data source: the military pay system.

The next steps: Plans for incorporating coordinated research into veteran suicide prevention strategies

Once a coordinated research apparatus is in place, the larger data sets obtained can be used to improve pre-existing veteran suicide prevention strategies. Location-based documentation may aid the coordination of veteran suicide prevention between the federal government and different local authorities, with the VAC and CAF playing a role in synchronizing and monitoring the process.

Given their proximity to grassroots veteran communities, municipal governments may be able to use this enlarged data to design strategies that increase accessibility to suicide prevention resources. They can do so by taking a “no wrong-doors” approach and complementing the services of the VAC-CAF strategy. For example, they could establish grassroots community wellness centers or municipal suicide-prevention taskforces. Likewise, they could offer veterans financial assistance and emulate the VAC’s services on a local, community level.

Provincial governments can also play a larger role in veteran suicide prevention, both by creating policies and supporting research. They can work alongside municipal actors to bring veteran suicide prevention services closer to veteran communities. They can also help the VAC’s location-based data collection within their provinces. The US Mayors’ and Governors’ Challenge to prevent veteran suicide may be a good example of a decentralized approach to the issue (SAMHSA, 2024).

For the VAC-CAF policymakers, better-coordinated research may open the doors to a bottom-up approach in veteran suicide prevention. One potential project might involve establishing peer-to-peer support systems between veterans and service members. While the VAC already has a similar pilot program focused on personalized services through the Veteran Service Assistants (a VAC staff member) (VAC, 2024), this recommendation suggests building stronger veteran communities. The goal is to expand these communities while integrating support and specialized care between veterans within said communities.

This recommendation will help to resolve the common issue of veterans having limited senses of community belonging and group identity (Thompson et al., 2019; Veterans Affairs Canada, 2024). It aims to do so while ensuring that necessary support services (usually provided at VAC institutions) come from more accessible sources who possess shared experiences and values related to military service and transition (Beehler et al., 2021). Such an initiative may also aid with employment opportunities for veterans.

Importantly, increased research coordination is beneficial. Data on the social determinants of suicide is necessary to gauge where the focus of the programs should be – particularly in rural areas where formal services are limited. Moreover, research on interconnected causes of suicidality shared between service members and veterans could prove useful in creating a trusting environment and in ensuring that proper support is provided (Beehler et al., 2021).

The role of VAC-CAF policymakers should be to ensure peer support providers are properly trained. Peer support providers must create clear boundaries between themselves and their peers, provide administrative oversight, and allocate necessary resources. These elements are crucial in building effective peer-to-peer suicide prevention programs (Beehler et al., 2021).

Additionally, the VAC’s Service Delivery branch must be well coordinated to address the main challenge of this peer support model: the emotional and physical burden on both the peer specialists and the veterans involved from having to discuss suicide in non-clinical settings (Huisman & van Bergen, 2019). Similar programs that were trialed in rural areas within the US had positive reactions from the veterans involved (Beehler et al., 2021; Pfeiffer et al., 2019). As a result of this study, the researchers observed a viability of the methods in preventing veterans’ suicide (Beehler et al., 2021; Pfeiffer et al., 2019). Such programs will also help the VAC meet its current budget-downsizing goals by delegating services to programs that only require indirect involvement (Government of Canada, 2024).

Figure 3: Percentage of veteran staff compared with non-veteran staff in the VAC’s workforce (Government of Canada, 2024).[1]

Conclusion

Veterans’ suicide remains an unresolved issue that continues to affect the integrity of the CAF and the VAC. The limitations of current policies are a result of a lack of coordinated research between the two institutions, causing a general scarcity of data and a disconnected study of the reasons behind service members’ and veterans’ suicides. To this end, this paper suggests that better-coordinated research by CAF-VAC researchers will improve future strategies on preventing veteran suicide.

[1] 175 compared to approx. 3800

References

Barrett, M., & English, A. (2014, June 4). Fallen on the field of honour? Attitudes of the Canadian public towards suicides in the Canadian military ~ 1914–2014. Canadian Military Journal, 15(4). http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vol15/no4/page22-eng.asp

Beehler, S., LoFaro, C., Kreisel, C., Dorsey Holliman, B., & Mohatt, N. V. (2021). Veteran peer suicide prevention: A community‐based peer prevention model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 51(2), 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12712

Berthiaume, L. (2019, April 16). Spike in Afghanistan-related suicides may be receding. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/forces-afghanistan-suicides-receding-military-1.5100119

Brewster, M. (2022, November 25). RCMP called to investigate multiple cases of veterans being offered medically assisted death. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/veterans-maid-rcmp-investigation-1.6663885

Brewster, M. (2024, March 1). Lawsuit over massive Veterans Affairs accounting error to cost Ottawa almost $1 billion. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/veterans-affairs-lawsuit-settlement-1.7130245

Brunet, A., & Monson, E. (2014). Suicide risk among active and retired Canadian soldiers: The role of posttraumatic stress disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(9), 457–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900901

Cooper, R., Assal, H., & Chiasson, S. (2017). Cross-national privacy concerns on data collection by government agencies (short paper). 2017 15th Annual Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST). https://doi.org/10.1109/pst.2017.00030

Ghobrial, A. (2024, April 25). CTE: Researchers believe widespread brain injury may contribute to veteran suicide rate. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/sci-tech/cte-researchers-believe-widespread-brain-injury-may-contribute-to-veteran-suicide-rate-1.6861457

Government of Canada . (2024, April 23). 1.0 demographics. Veterans Affairs Canada. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/news-and-media/facts-and-figures/10-demographics

Government of Canada. (2024, April 11). 13.0 human resources. Veterans Affairs Canada. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/news-and-media/facts-and-figures/130-human-resources

Government of Canada. (2024, September 10). Departmental plan at a glance 2024–2025. Veterans Affairs Canada. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/about-vac/reports-policies-and-legislation/departmental-reports/departmental-plans/departmental-plan-2024-2025/departmental-plan-glance-2024-2025

Government of Canada. (2017, October 13). Executive summary: Joint suicide prevention strategy. Department of National Defence. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/reports-publications/caf-vac-joint-suicide-prevention-strategy/exec-summary.html

Huisman, A., & van Bergen, D. D. (2019). Peer specialists in suicide prevention: Possibilities and pitfalls. Psychological Services, 16(3), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000255

Jalles, J. T., & Andresen, M. A. (2015). The social and economic determinants of suicide in Canadian provinces. Health Economics Review, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-015-0041-y

Jamieson, S. K., Cerel, J., & Maple, M. (2024). Impacts of exposure to suicide of a military colleague from the lived experience of veterans: Informing postvention responses from a military cultural perspective. Death Studies, 48(7), 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2023.2261408

Kirkbride, J. B., Anglin, D. M., Colman, I., Dykxhoorn, J., Jones, P. B., Patalay, P., Pitman, A., Soneson, E., Steare, T., Wright, T., & Griffiths, S. L. (2024). The social determinants of mental health and disorder: Evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry, 23(1), 58–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21160

Mahar, A. L., Aiken, A. B., Whitehead, M., Tien, H., Cramm, H., Fear, N. T., & Kurdyak, P. (2019). Suicide in Canadian veterans living in Ontario: A retrospective cohort study linking routinely collected data. BMJ Open, 9(6).

Raycraft, R. (2022, July 24). Pride in Canada’s military has eroded over the past year: Report. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-military-survey-1.6529074

Rudnick, A., Nolan, D., & Daigle, P. (2022). Sharing of military veterans’ mental health data across Canada: A scoping review. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 8(2), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.3138/jmvfh-2021-0064

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024, October 23). Governor’s and mayor’s challenges to prevent suicide among service members, veterans, and their families. https://www.samhsa.gov/smvf-ta-center/mayors-governors-challenges

Thompson, J. M., Dursun, S., VanTil, L., Heber, A., Kitchen, P., de Boer, C., Black, T., Montelpare, B., Coady, T., Sweet, J., & Pedlar, D. (2019). Group identity, difficult adjustment to civilian life, and suicidal ideation in Canadian Armed Forces veterans: Life after service studies 2016. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 5(2), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.3138/jmvfh.2018-0038

US Department of Veteran Affairs. (2024). National veteran suicide prevention: Annual report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2024/2024-Annual-Report-Part-1-of-2_508.pdf

VanTil, L., Kopp, A., & Heber, A. (2021). 2021 veteran suicide mortality study: Follow-up period from 1975 to 2016 [PDF]. Veterans Affairs Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2022/aca-vac/V3-1-9-2022-eng.pdf

Veterans Affairs Canada. (2024). Delivering service excellence: A review of Veterans Affairs Canada’s service delivery model [PDF]. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/about-vac/reports-policies-and-legislation/departmental-reports/delivering-service-excellence