Hamish Denholm, Simon Fraser University | July 11, 2025

Right-Wing Extremist (RWE) Penetration of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF)

Concerns and Policy Recommendations to Inform Immediate Action

home / policy briefs / hamish denholm

time to read: 13 min

Photo: Canadian Armed Forces Imagery Technician

Executive Summary

This policy brief explores the application of UK counter-extremism strategies within the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) for addressing the rising concern of right-wing extremism (RWE). In particular, it examines how proactive measures such as social media surveillance, collaboration with civilian organizations, and an expanded monitoring timeline could enhance the CAF’s response to the growing threat. The key recommendation is to shift from a reactive to a proactive stance when identifying and addressing extremist behaviours. This will require a more integrated approach that includes both military and civilian expertise.

This brief draws on successful counter-extremism models from the UK and US, which have emphasized intelligence-sharing and early intervention, especially in monitoring social media platforms for signs of radicalization. By extending this monitoring of CAF personnel to five years pre- and post-service, this brief suggests a broader scope for identifying long-term extremist affiliations. It highlights these proactive identification methods, particularly those focused on screening during pre-service recruitment and post-service transition periods. It further reinforces the importance of social media monitoring. This will allow the CAF to mitigate the risk of extremism before it becomes entrenched within the ranks.

Adopting UK and US strategies will enable the CAF to not only better combat RWE, but also strengthen its overall mission-effectiveness by maintaining a commitment to a diverse and neutral force. This strategy requires a holistic approach, drawing on both military expertise and civilian partnerships, to ensure a robust and sustainable response to emerging threats in the security environment.

Introduction

The effectiveness and operational readiness of the CAF's rank-and-file and senior leadership hinges on their ability to function as a unified and cohesive force, regardless of race, class, ethnicity, gender, or religion. However, the rise of RWE within the ranks has posed a significant threat to this unity. Instances of racist ideologies, xenophobia, and discriminatory behaviour have not only undermined the CAF’s core values of diversity and inclusivity but have also compromised operational and interoperability efficiency.

RWE presents a multifaceted challenge. It influences not only the operational effectiveness of the CAF, but also public trust. It also negatively affects the CAF’s ability to contribute to regional and national stability and exposes security weaknesses within the Forces.

National Security Concerns

The infiltration of RWE within the CAF poses a substantial national security risk. The concern lies in the potential for CAF personnel to exploit their combat expertise and weapons training to engage in violent acts against Canadian citizens, potentially in collaboration with Violent Transnational Social Movements (VTSMs) (CASIS-Vancouver, 2021). For example, ‘the Base’ is a VTSM group that is linked to former-CAF member, Patrik Mathews, who planned high casualty attacks against civilian targets (Shanti, 2024). This example, one of many, underscores the profound and severe penetration of RWE within the CAF.

Public Trust

Public trust is a vital for CAF, especially in a decade characterized by the pronounced deterioration of international peace and stability. Despite still retaining a relatively positive outlook from the public until now, the CAF is experiening s a deterioration which could be attributed to the increasing prevalence of RWE (Earnscliffe Strategy Group, 2022). This is particularly concerning because RWE has been associated with elevated frequencies of violent terrorism from VTSM collectives.

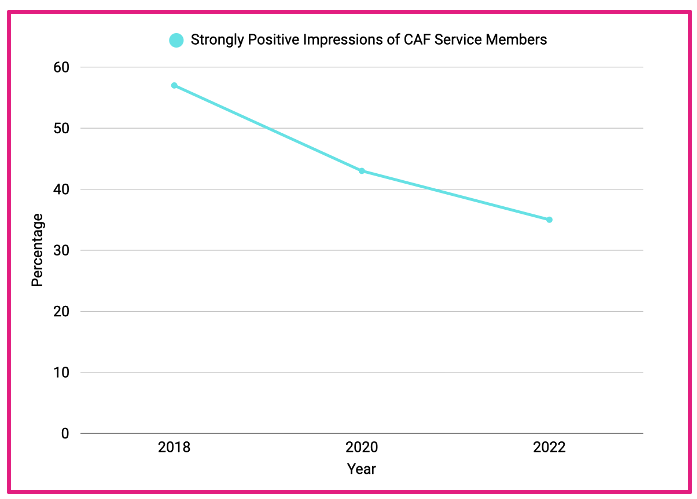

For instance, a report by the Earnscliffe Strategy Group (2022) prepared for the Department of National Defence (DND) in 2022 found that:

“Although overall impressions of the CAF are mostly positive or neutral, tracking data demonstrates that the degree of positivity towards the CAF is lower. For example, while 76% view those who serve in the CAF positively, 35% say their impression of those who serve is strongly positive, compared to 43% in 2020 and 57% in 2018” (p. 5).

Figure 1: Impressions of CAF Members From 2018 – 2022 (Earnscliffe, 2022)

The Earnscliffe Strategy Group (2022) also found that over half of racialized individuals in the study expressed concerns about systemic racism – a an issue related to the emergence of RWE (Earnscliffe Strategy Group 2022). This creates the possibility for public trust and RWE proliferation becoming an operational effectiveness issue. Recruitment from a diverse demographic will be directly affected by perceived failures regarding the CAF’s commitment to inclusivity. While the report does not explicitly connect RWE to this downward trend, it does suggest a worsening public perception of the CAF. This worsening perception highlights the increasing vulnerability of the CAF’s reputation—a fragility likely to deepen as RWE continues to rise and become more exposed.

This brief emphasizes the likelihood that RWE has accelerated the decay of public trust in the CAF, a trend that requires urgent consideration to avoid dangerous outcomes in security and operational frontiers. The government, the Prime Minister, his cabinet, the CAF and its Chief of Personnel are all key stakeholders in the investigation and resolution of RWE.

Policy Issue

The rise of RWE within the CAF exposes critical vulnerabilities in existing policies aimed at maintaining unity, public trust, and operational readiness. Current measures, which focus primarily on pre-service vetting and fragmented reporting systems, fail to address the continuous threat posed by extremist affiliations during and after service. This policy gap not only risks the internal culture and diversity of the CAF becoming compromised but also represents a significant national security concern, as evidenced by cases of former personnel participating in violent transnational social movements.

With public trust in the CAF eroding, particularly among racialized groups, and the potential for extremist-trained individuals to engage in violent acts, the need for a proactive, comprehensive policy response has become urgent. Strengthening recruitment screening, enhancing reporting protocols, and establishing ongoing monitoring are essential steps to ensure the CAF can effectively counteract RWE and safeguard both its integrity and Canada’s security.

Analysis

The Trend in RWE Membership and Affiliation in Canada and the CAF Reserves

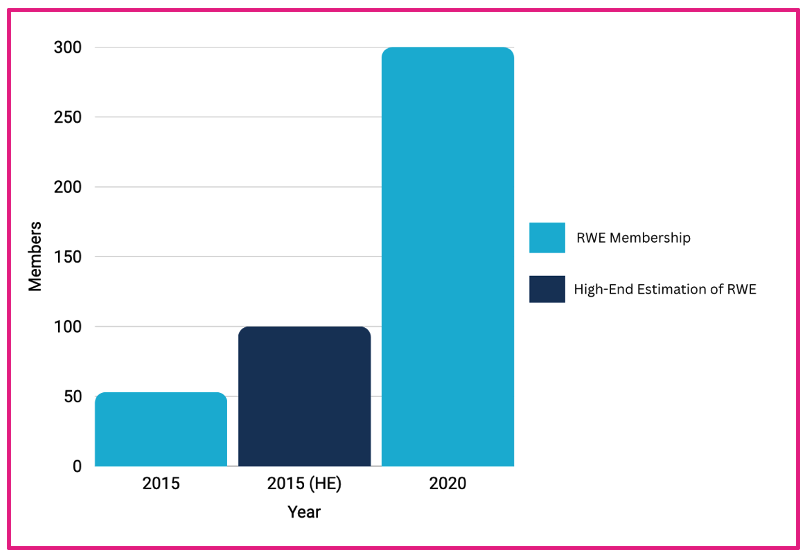

A report by the DND and Canadian Forces College found that “the number of identified hate groups in Canada has tripled in a short period of time” (Tebbutt, 2021). The number of identified white supremacist groups that were operating in Canada rose from approximately 80-100 in 2015 to 300 in 2020. In other words, there was a 200-275% increase in RWE activities in Canada in only five years. In the context of the CAF itslef, from 2013 to 2018, the Military Police Intelligence Report found that 53 CAF members had connections with RWE groups.

Figure 2: RWE Membership in Canada & High-End Estimation of RWE in 2015

The actual number of CAF members reported to have connections to RWE groups is thought to be significantly greater due to the pressures of keeping their views covert to avoid fatal career penalties. Identifying individuals with RWE sympathies may be easier in the Primary Reserve than in the Regular Force. Unlike full-time members, reservists often have civilian jobs, lowering the professional risks associated with expressing extremist views (Tebbutt, 2021). They also face fewer off-duty regulations and can leave service at will, unlike regular personnel who are contractually bound. These factors – along with shorter service periods and less institutional oversight – make the Primary Reserve a potentially more attractive setting for those with RWE ideologies. It is an issue that this is not taken into account when RWE in the CAF is represented statistically.

Why RWE?: Internal Culture and the 'Warrior Identity'

The concept of the "warrior identity" within the CAF plays a crucial role in shaping internal culture, often reinforcing systemic issues like RWE. The warrior identity is historically rooted in traditional military and social values, which emphasize traits such as masculinity, heteronormativity, and physical toughness (Eichler, 2023). This identity is associated with a notion of "the real soldier," which marginalizes individuals who do not conform to these standards. Racialized individuals, women, non-binary people, 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals, and people with disabilities are particularly impacted. As such, the CAF culture inadvertently perpetuates discriminatory beliefs and behaviours, making it more susceptible to the infiltration of RWE ideologies.

This narrow and exclusionary understanding of what it means to be a soldier creates a cultural climate that can be exploited by extremist groups. Take, for example, the case of Master Corporal Patrik Mathews, who was found to have connections with white a supremacist group. According to Shanti (2024), his views were likely shaped and supported by a military environment that valorizes certain "warrior" values while sidelining diversity and inclusivity.

The persistence of such an identity associated within the CAF not only harms its cultural inclusivity but also threatens its operational cohesion and effectiveness. Soldiers who feel excluded or marginalized due to their identity may be less likely to trust their comrades, which ultimately undermines unit morale and readiness (Knight, 2021). Addressing the internal culture and transforming the warrior identity to reflect more inclusive and diverse values is a critical step toward reducing the spread of RWE and fostering a more unified and effective CAF.

Institutional Resistance and Accountability Challenges

A significant challenge in combating RWE within the CAF is the institutional resistance to fully acknowledge and address the issue. While RWE activity is apparent, certain segments of the CAF remain hesitant to confront it, fearing disruption of traditional values and unit cohesion (Knight, 2021). This resistance is exacerbated by a lack of robust accountability mechanisms that would hold individuals and units responsible for addressing RWE infiltration. Leadership often avoids confronting extremist views as they are more concerned about damaging the CAF’s reputation. Cultural values like loyalty can lead to overlooking problematic behaviour, allowing RWE sympathies to persist.

Additionally, the internal reporting mechanisms for identifying extremist behaviour, particularly among reservists, are fragmented and lack necessary protections for whistleblowers, which contributes to underreporting and delayed responses. While the Public Servant Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA) is designed to safeguard whistle-blowers from reprisal, its effectiveness is compromised when RWE has penetrated leadership roles as it has in the CAF – particularly those responsible for addressing whistleblower reports (Government of Canada, 2024). A critical review and audit of internal investigations is needed to address deficiencies in the CAF's ability to unilaterally remediate incidents (Walden University, n.d.). Without clear accountability structures, personnel are discouraged from reporting, allowing extremist behaviours to go unchecked.

To address these challenges, the CAF must improve its reporting systems, enhance whistleblower protections, and establish more consistent accountability frameworks. By prioritizing transparency and proactive responses, the CAF can foster a culture of accountability that actively identifies and addresses extremist behaviour, ultimately strengthening the military’s integrity and effectiveness.

Policy Recommendations

Policy actions to circumvent RWE within the CAF should consider the following multifaceted approach. The CAF should also be multi-tiered and flexible in its investigatory strategies.

Social Media Monitoring

The CAF’s response to RWE has been a reactionary strategy rather than a proactive one (The Canadian Association for Security and Intelligence Studies Vancouver, n.d.). Current policy is inadequate, failing to act as a deterrent to RWE behaviours. This is because disciplinary actions are taken after an incident has occurred, and often only if it is a large enough case to draw public attention. Social media, in particular, has proven to be a powerful conduit for RWE ideologies, enabling their infiltration into CAF ranks and dissemination from within (Metz, 2021). Therefore, to enhance the CAF’s proactiveness and ability to identify and monitor RWE within its ranks, greater attention should be devoted to understanding the personal lives of its members by prioritizing social media monitoring.

The CAF has already implemented policies to monitor its members' online activities through Operation Fence Post, which primarily aims to prevent the unauthorized disclosure of classified information online (Pugliese, 2024). However, the monitoring infrastructure established under Operation Fence Post could be effectively expanded to support a policy aimed at tracking and addressing right-wing extremist rhetoric on social media, while utilizing the same foundational mechanisms to counteract potential radicalizationt. The U.S. Armed Forces have begun to implement social media pilot programs to watch service members for “concerning behaviours,” providing a model that could be adapted to the Canadian context (Klippenstein, 2021; Metz, 2021).

To strengthen efforts to counter RWE through social media, The U.S. has incorporated partnerships with private, civilian, and non-military organizations (Klippenstein, 2021). This approach aims to enhance detection capabilities and overcome potential bureaucratic and institutional biases within the military. The incorporation of the civilian sphere is an important step if the Canadian implementation of a similar policy is to be effective, as the CAF has proven to be ineffective in its ability to unilaterally circumvent RWE. The implementation of a more collaborative deployment of social media surveillance can involve branches of the Canadian Secret Intelligence Service (CSIS), Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the CAF, and private tech firms like Babbel Street whom the Pentagon already works with in their pilot program (Klippenstein, 2021).

Social Media Monitoring: the Vetting Process

Monitoring and investigation of CAF personnel as part of the vetting process can begin as soon as an individual applies to join CAF. The scope of investigation and monitoring should include activity five years prior to application, the duration of employment, and five years following any resignation, dismissal, or termination from the CAF. The monitoring approach should align with the standards set in the Defence Administrative Orders and Directives (DAOD 5019-2), which mandates a continuous review process for officers and non-commissioned members within the CAF (Government of Canada, 2022a). The review is based on conduct deficiencies that might compromise professional standards. Modifications to the DAOD, such as the recommended extension of monitoring to five years before, during, and after, employment in the CAF, and focusing on extremist behaviour, would allow for a more comprehensive dataset to assess personnel behaviour outside of active service. This broader timeline enhances the ability to identify patterns and potential risks that might not be evident when looking across the time of active duty alone, providing a broader picture of an individual’s suitability for service.

To address the presence of RWE within the CAF, this recommendation involves adapting and merging the existing DAOD with Operation Fence Post to include expanded social media monitoring and more rigorous background checks. The strategy prioritizes proactive identification of RWE behaviours by integrating surveillance of public social media activity with existing CAF intelligence and policing efforts. Under this plan, the expanded DAOD and Operation Fence Post would enable CAF Intelligence and Military Police to jointly monitor the public social media profiles of CAF personnel for indicators of RWE, such as extremist symbols, language, and associations. This monitoring strategy would adhere to legal standards for public information access while strengthening internal mechanisms to detect and address potential radicalization. In instances where the Parliament ratifies the Emergencies Act, certain privacy protections may be temporarily limited, allowing the flexibility for broader investigation when needed.

The timeline for this adaptation should begin with a policy review and update within the next six months, followed by a phased implementation of social media monitoring within a 12-month period. During this time, the CAF Chief of Intelligence, CSIS, and the Military Police would assume primary responsibility for overseeing the expanded monitoring policy. This would include designing and delivering specialized training for intelligence and policing personnel to enhance their ability to identify and interpret RWE-related content effectively (this will be further expounded in the second policy recommendation of this briefing). This approach allows for a comprehensive yet targeted expansion of CAF’s capabilities to detect RWE, thereby safeguarding the organization’s integrity and fostering a secure and inclusive environment across the armed forces.

Identification and Intervention of RWE and Education of CAF Personnel

This policy recommendation is intended to work in conjunction with the initial policy proposal, which advocates for enhanced social media monitoring and vetting provisions. The success of social media monitoring requires personnel to have adequate training on the identification of RWE. Much of the CAF’s leadership is apprehensive to act on RWE primarily because of difficulties “understanding far-right ideology and how to respond” (Metz, 2019-2021).

The proposed policy would make education on the identification of RWE and other forms of extremism mandatory prerequisites for the successful graduation of CAF personnel during basic training. This policy recommendation is modelled on efforts conducted by the United Kingdom (UK), a Canadian ally, who has developed mandates to train government personnel to effectively recognize individuals with extremist inclinations and behaviours (Tebbutt, 2021). Although the UK’s policy is not fully intended for a military application, the infrastructure remains useful for the context of a military deployment. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Prevent program, which aims to thwart individuals from engaging in terrorism and radicalization, can be used in the CAF’s effort to circumvent RWE within its ranks. The Prevent program has been used in the education sector throughout England for the “provision of training, guidance and support…to handle safeguarding incidents related to terrorism” (HM Government, 2023).

Implementing this program into the CAF’s basic training will allow CAF leadership to implement yet another UK program called the Desistence and Disengagement Program (DDP) (HM Government, 2023). DDP “provides tailored interventions that support individuals to stop participating in terrorism-related activity (desist) and move away from terrorist ideology and ways of thinking (disengage)” (HM Government, 2023). The DDP could be adapted for Canadian military use, focusing on personnel with prior extremist affiliations or those assessed as being at risk, to enhance the ability of CAF personnel to identify RWE. The program would include counselling, ideological intervention, and peer mentoring to disengage individuals from extremist ideologies and reintegrate them into military culture. It is important to note that military reintegration should be at the discretion of the Chief of Personnel; egregious offences should be sent to a tribunal or criminal court before or after intervention, prohibiting reinstatement if necessary. The CAF is encouraged to seek partnerships with civilian experts and institutions in de-radicalization for their added expertise and support.

The Chief of Personnel will oversee the initial assessment and collaboration with UK experts in the first 0-6 months. The CAF Training Command will develop the RWE training and DDP from montgs 6-12. In months 12-18, the Director of Military Training will pilot the program, working with civilian experts. The CAF Evaluation Team will review the program’s effectiveness in months 18-24, with the Director of Training and Education refining it for full integration. After 24 months, Ongoing Training Units, led by the Director of Personnel Development, will manage continued professional development and expand the DDP. Since this policy recommendation calls for changes to CAF training standards, the timeline for this policy implementation is based on the CDS/DM Directive for CAF Reconstitution (Government of Canada, 2022b). This policy implementation will take place during the “Recover” phase of the reconstitution’s “Scheme of Manoeuvre”, which is supposed to take place from 2022-2025 with exceptions (Government of Canada, 2022b).

References

CASIS-Vancouver. (2021). Right-wing extremism elements in the Canadian Armed Forces. The Journal of Intelligence, Conflict, and Warfare, 2(2), 87-94. https://doi.org/10.21810/jicw.v2i2.1059

Earnscliffe Strategy Group. (2022). Views of the Canadian Armed Forces – 2021-2022 Tracking Final Report. Department of National Defence. https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/301/pwgsc-tpsgc/por-ef/national_defence/2022/084-20-e/POR084-20-Report-EN.pdf

Eichler, M. & Brown, V. (2023). Getting to the root of the problem: Understanding and changing Canadian military culture [Working paper]. Transforming Military Cultures (TMC) Network. https://www.msvu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Eichler-and-Brown_final_May-1-2023.pdf

Government of Canada. (2022a, October 6). CDS/DM directive for CAF reconstitution. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/policies-standards/dm-cds-directives/cds-dm-directive-caf-reconstitution.html

Government of Canada. (2022b, June 20). DAOD 5019-2, administrative review. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/policies-standards/defence-administrative-orders-directives/5000-series/5019/5019-2-administrative-review.html

Government of Canada. (2024, July 10). Submit a disclosure of wrongdoing. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/contact-us/whistleblowing/submit-disclosure-wrongdoing.html

HM Government. (2023, July). The United Kingdom’s Strategy for Countering Terrorism 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/counter-terrorism-strategy-contest-2023

Klippenstein, K. (2021, May 17). Pentagon plans to monitor social media of military personnel for extremist content. The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/2021/05/17/military-pentagon-extremism-social-media/#:~:text=Pentagon%20Plans%20to%20Monitor%20Military%20Social%20Media%20for%20Extremism

Knight, T. (2021). Systemic racism in the Canadian Armed Forces. Government of Canada. https://www.cmrsj-rmcsj.forces.gc.ca/io-oi/pub/2021/pub_2021-1-fra.asp

Metz, A. J. (2021). Imbalance of policy and threat: Social media and the Canadian Armed Forces. North York: Canadian Forces College.

Pugliese, D. (2024, July 31). Canadian Forces monitoring personnel's social-media accounts in operation codenamed Fence Post. Ottawa Citizen. https://ottawacitizen.com/news/national/defence-watch/canadian-forces-monitoring-social-media-fence-post

Shanti, D. (2024). News media and the military: Portraying and responding to right-wing extremism in the Canadian Armed Forces. Master’s Thesis, Calgary: University of Calgary.

Tebbutt, T.L. (2021). Cultural perspectives of right-wing extremism in the Canadian Armed Forces. Department of National Defence. https://www.cfc.forces.gc.ca/259/290/23/305/Tebbutt.pdf

The Canadian Association for Security and Intelligence Studies Vancouver. (n.d.). Right-wing extremism in the Canadian Armed Forces. https://casisvancouver.ca/press-releases/right-wing-extremism-in-the-canadian-armed-forces/

Walden University. (n.d.). Internal investigations: Common mistakes HR professionals can make. https://www.waldenu.edu/online-masters-programs/ms-in-human-resource-management/resource/internal-investigations-common-mistakes-hr-professionals-can-make#:~:text=Investigations%20that%20take%20too%20long,complaining%20employee